Modern historians and anthropologists have fascinated themselves with the study of the Greeks. One of the earliest and most advanced civilizations of the time, the ancient Greek nation possessed a unique feature: it was divided into multiple city-states. And, just like in early American history, regional and local identities were often stronger than national ones.

Since the ancient Greeks did not act as a unified political entity, discovering how they perceived themselves was and still is a politically salient question. Modern scholars often forward the belief that the ancient Greeks were not a unified ethnic group, but rather a loose connection of religiously and linguistically similar city-states that were later formed into a cohesive group. To offer a refute of this popular opinion, I will explore the differences between Greeks and non-Greeks through a thorough consultation of the philosophers themselves, primarily Plato’s Republic and Menexenus.

Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle – the three preeminent Greek political philosophers – were all Athenians. Athens had led the Delian League against the Persians, while soon thereafter being embroiled in the Peloponnesian War against the Spartans and their allies. During the Greco-Persian War, the Athenians were offered an ultimatum by the Persians: either join us or be destroyed.

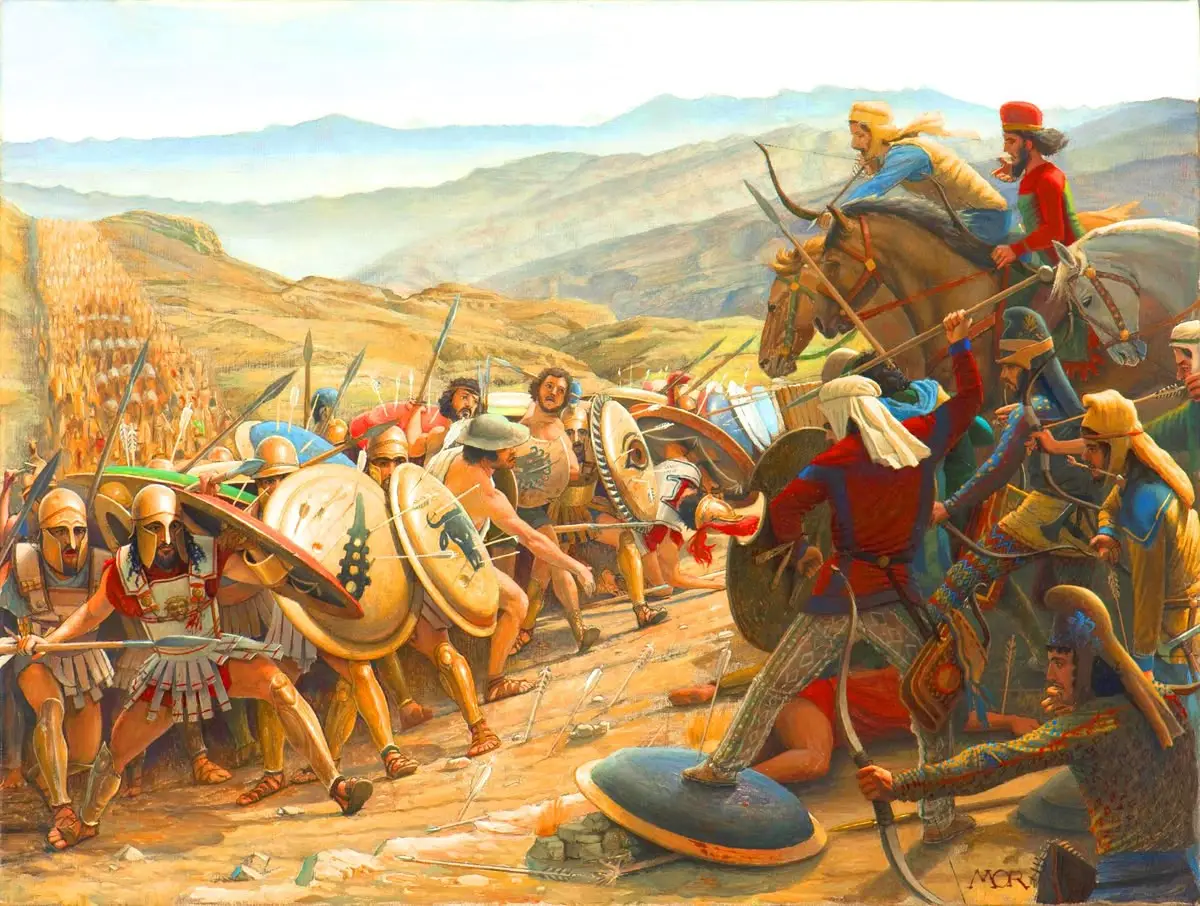

Tensions over Persian expansion into Greek-influenced Ionia and Greek support for a revolt against Persian rule sparked the Greco-Persian War.

Tensions over Persian expansion into Greek-influenced Ionia and Greek support for a revolt against Persian rule sparked the Greco-Persian War.

The Athenians chose to go toe to toe with the most powerful army in the known world, a decision which may certainly have doomed Athens and the rest of the Hellenic world to slavery and destruction. Their reasoning was simple: the Athenians had a common cause with their fellow Greeks simply because they were all Greeks.

Herodotus writes, “For there are many great reasons why we should not do this, even if we so desired; first and foremost, the burning and destruction of the adornments and temples of our gods, whom we are constrained to avenge to the utmost rather than make pacts with the perpetrator of these things, and next the kinship of all Greeks in blood and speech, and the shrines of gods and the sacrifices that we have in common, and the likeness of our way of life, to all of which it would not befit the Athenians to be false.”

The Athenians supported the notion that the Greeks constituted one cohesive nation because they shared a common ancestry, language, religion, and culture. This passage from Herodotus is one of the most explicit definitions of ethnicity, which encompasses all of the Hellenic world, transcending local traditions, dialects, and gods.

Herodotus defines a nation in such a way that the Greeks can very easily distinguish themselves from non-Greeks. A qualification based on heritage, culture, genetics, language, and religion could be applied to any people, but in the case of the Greeks, these qualifiers were very important components of the shared Hellenic identity.

Herodotus, often called the “Father of History,” was an ancient Greek historian who chronicled the events of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Herodotus, often called the “Father of History,” was an ancient Greek historian who chronicled the events of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Likewise, Plato mentions the Greeks as a distinct group in the Republic. His belief in the existence of the Greek nation is so strong that he engages in a long dialogue about the Greekness of his ideal city.

Glaucon asks, “Do you think it is just for Greeks to enslave Greek cities, or, as far as they can, should they not even allow other cities to do so, and make a habit of sparing the Greek race, as a precaution against being enslaved by the barbarians?” to which Plato responds, “It’s altogether and in every way best to spare the Greek race.”

Plato affirms that Greeks ought not to enslave each other, and they should continue to treat each other well in times of war to protect themselves from the barbarians. However, Plato goes even further by saying that the Greeks ought not to enslave each other at all, and that the whole Greek nation acting with respect and with a sense of patriotism is better in every way.

Of course, war was a common occurrence in the Greek world. Greek city-states would often fight one another more than they would fight against a foreign enemy. The Greeks forming the Delian League was something of an anomaly, considered to be the first instance of the Greek city-states acting as one entity. Plato’s Republic contains multiple passages about the interaction of the ideal city and the rest of the Greek world, emphasizing the city’s Greek character and discussing the potential of conflict between the city and its enemies. “When Greeks do battle with barbarians or barbarians with Greeks, we’ll say that they’re natural enemies and that such hostilities are to be called war. But when Greeks fight with Greeks, we’ll say that they are natural friends, and that in such circumstances Greece is sick and divided into factions, and that such hostilities are to be called civil war.”

Frequent conflicts between Greek city-states stemmed from intense rivalries, competition for resources, and differing political systems.

Frequent conflicts between Greek city-states stemmed from intense rivalries, competition for resources, and differing political systems.

Although the Greeks fought each other frequently, Plato believed that it was best for Greeks in the ideal city to treat each other with respect and to minimize conflict whenever possible. Barbarians, on the other hand, were not given this courtesy.

Plato’s beliefs about civil conflict and war were not merely pragmatic or idealistic methods of minimizing conflict, but a profound understanding of the differences between Greeks and non-Greeks. These differences can be understood in the context of Plato’s recent past, as the Republic was written in roughly 375 BC, and the Greco-Persian wars took place around 100 years prior, from roughly 499-479 BC.

With previous wars occurring only a few generations prior, the understanding of the cohesive Greek nation would surely be more established, and the differences between the Greeks and foreigners certainly more pronounced in the aftermath of the war. However, it is important to emphasize that the identities are not a product of the war itself, even if they may have been strengthened by it.

In Book 5 of The Republic, Socrates explains how the ideal city is both politically and culturally Greek.

Socrates: “What about the city you’re founding? It is Greek, isn’t it?” Glaucon: “It has to be.” Socrates: “Then won’t your citizens be good and civilized?” Glaucon: “Indeed they will.” Socrates: “Then won’t they love Greece? Won’t they consider Greece as their own and share the religion of the other Greeks?” Glaucon: “Yes, indeed.”

This reveals how Greek identity is assumed to be a precondition for moral and civic virtue. Socrates also linked cultural belonging to ethical behavior, suggesting that only a city composed of Greeks can cultivate the virtues required for justice. The citizens are not only expected to uphold Greek values but also to “consider Greece as their own and share the religion of the other Greeks,” further emphasizing the city’s alignment with a broader pan-Hellenic identity.

This passage illustrates how Plato embeds ethnic and cultural assumptions within his political theory, marking a clear boundary between the “civilized” Greek and the foreigner. It was assumed that the foreigners, who did not practice philosophy as the Greeks did, were not capable of creating or inhabiting the ideal city; only the philosophically minded Greeks were capable of this. By anchoring the just city in a specific and distinct Greek identity, Plato supports the notion that virtue and philosophical thought are not universal traits but are inextricable from the culture, and by extension, the ethnicity of the Greeks.

Life in ancient Athens during Plato’s time was vibrant and intellectually rich, marked by democratic debate, artistic achievements, and philosophical exploration.

Life in ancient Athens during Plato’s time was vibrant and intellectually rich, marked by democratic debate, artistic achievements, and philosophical exploration.

Another Platonic dialogue it would be prudent to examine is Menexenus. The dialogue of Menexenus begins with Plato recounting a funeral oration that he learned from Aspasia, a friend of Pericles. Eventually, Plato begins to give the funeral oration, where he describes the patriotic fervor of the Athenians.

Although Menexenus is believed to be mostly satirical, it does give us a keen insight into the self-image of the Greeks and how they perceived their non-Greek counterparts. Plato begins the oration by establishing the autochthonous nature of the Greeks: “And first as to their birth. Their ancestors were not strangers, nor are these their descendants sojourners only, whose fathers have come from another country; but they are the children of the soil, dwelling and living in their own land.”

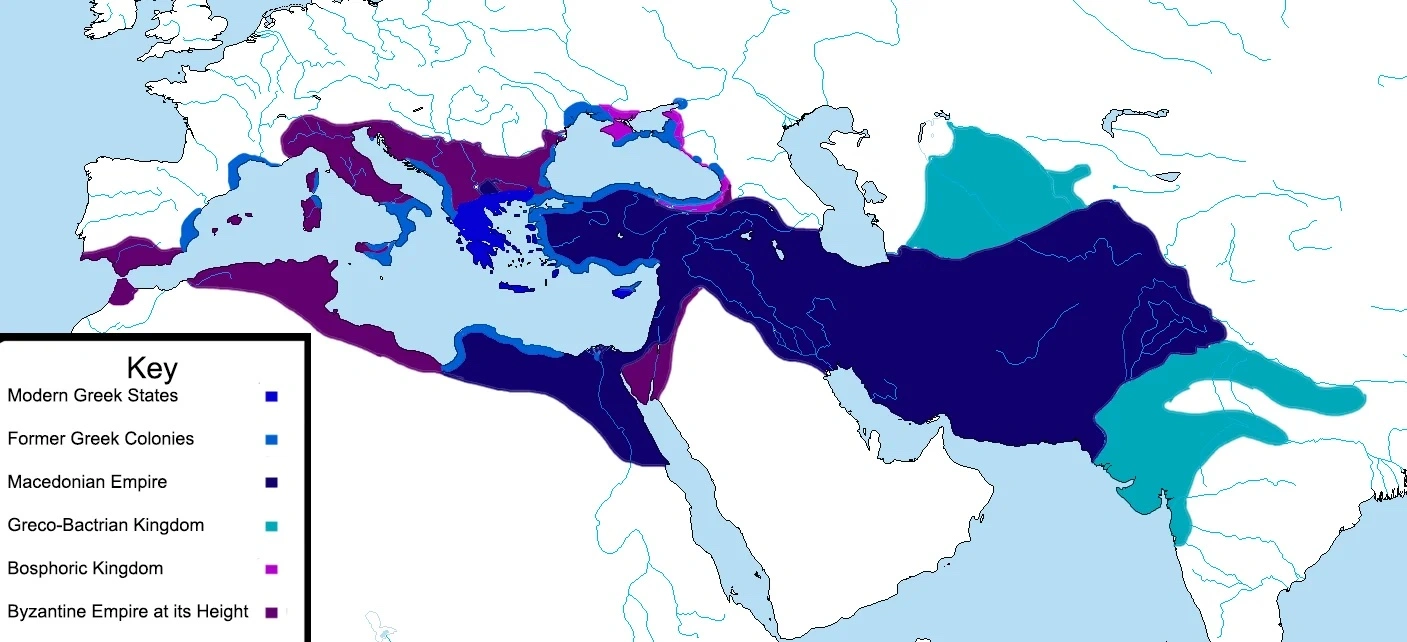

Here, Plato’s claim that the Greeks are children of the soil should not be taken literally, but this passage does reflect the idea that the Greeks are native to the Greek land. While many Greek colonies existed in “Cyprus, and… Egypt,” the Hellenic homeland was a tangible and real one, bound by the many traits that distinguish Greeks from foreigners. Greeks had their homeland to which they were natives, and the foreigners had theirs as well.

Menexenus continues on, emphasizing the relationship between Greeks and their land, emphasizing the fact that the Greeks have a homeland. As the previous passage mentions, the Greeks did not come and displace any previous population, but they built the city-states that dominated the Aegean. “The country which brought them up is not like other countries, a stepmother to her children, but their own true mother; she bore them and nourished them and received them, and in her bosom they now repose.”

The Greek language spread rapidly throughout the Mediterranean in ancient times through trade, colonization, and the cultural influence of the expanding Greek city-states.

The Greek language spread rapidly throughout the Mediterranean in ancient times through trade, colonization, and the cultural influence of the expanding Greek city-states.

Although the connection to the land may seem abstract, I contend that the Greeks believed that their role as the original inhabitants was just as important as, say, their language or culture.

Herodotus also emphasized the shared ancestry of the Greeks in his writings, which Plato built upon by connecting the shared ancestry to a shared habitation of the land. By connecting a shared ancestry to the land, the Greek philosophers emphasized Greek autochthony and the legitimacy of the claim of ethnic distinction and territorial belonging.

This notion distinguished the Greeks from foreigners not only by language or religion, but through a shared ancestral bond to the land, reinforcing a collective identity rooted in both place and lineage. Moreover, Athens was not just a city-state; it reserved political participation for Greek Athenians, and political rights were not available to resident aliens or any sort of foreigner. “Such was the natural nobility of this city, so sound and healthy was the spirit of freedom among us, and the instinctive dislike of the barbarian, because we are pure Hellenes, having no admixture of barbarism in us.”

The claim of lineage and ethnicity was not only politically salient at the time; it was considered to be the foundation of the Greek people, and the main distinguishing characteristic between Greeks and non-Greeks. Indeed, there was no concept of assimilation in ancient Greece. Even if someone were to learn Greek and adopt the gods of the city, they would still be an alien to the Greeks.

Plato went so far as to criticize people who would be considered “Ellinomatheis,” which means a student of Greek, believing that even those who may possess Greek culture and speak the Greek language, while not being Greek by nationality or ethnicity. As articulated in the Menexenus, Plato states, “For we are not like many others, descendants of Pelops or Cadmus or Egyptus or Danaus, who are by nature barbarians, and yet pass for Hellenes, and dwell in the midst of us; but we are pure Hellenes, uncontaminated by any foreign element, and therefore the hatred of the foreigner has passed unadulterated into the life-blood of the city.”

Clearly, ancient Greeks highly valued ethnic purity, emphasizing shared ancestry, language, and customs as key to defining Greek identity.

Clearly, ancient Greeks highly valued ethnic purity, emphasizing shared ancestry, language, and customs as key to defining Greek identity.

This assertion of ethnic purity reinforced the Athenian conception of their superiority and underscored the role of cultural and racial homogeneity in the Greek self-identity. The distinction between Greeks and foreigners was not only a politically salient rhetorical device used in the funeral oration, but also representative of the common understanding of the tangible divide between Greeks and foreigners.

Moreover, such an emphasis on being “uncontaminated by any foreign element” reveals the centrality of purity in the Athenian and, by extension, the Greek sense of collective identity. While Greek city-states like Athens maintained distinct regional and local identities, the notion of ethnic purity and the rejection of foreign influences played a pivotal role in the eventual formation of a more unified Greek identity, something that wholly transcended the local identities that characterized Greek political organization until the formation of the modern Greek state.

Some of the alternative theories championed by contemporary scholars suggest that the ancient Greeks reinforced linguistic cleavages to distinguish themselves from their neighbors. “The Greeks relied mainly on barbarizing others in order to highlight their identity, and this approach led to racism that was obvious in the writings of their most famous philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle. However, this racism began to fade at the beginning of the Hellenistic era, with a new understanding of identity as a shared education and culture rather than race or nationality.”

It is my contention that Salem misinterpreted various passages from Characters by Theophrastus, where it is posited, “why it is that we Greeks are not all one in character, for we have the same climate throughout the country, and our people enjoy the same education.” This theory has been echoed by many modern scholars, refuting the idea of a coherent Greek ethnicity or race, arguing instead that the separate city-states were formed into an ethnicity based on linguistic and religious similarities, while sharing little genetic or racial unity. Although the anthropological claims of ancient racial coherence are far from resolved, the claims about educational and cultural similarities across city-states lack foundation in historical fact.

Additionally, I believe that Salem’s interpretation may be a misunderstanding of Characters, which is a study of inter-Hellenic diversity and not an argument used to divide Greeks into separate groups. Most people already know that Athens and Sparta had notoriously divergent constitutions and educational systems. While Spartan education emphasized strength, obedience, and military service, the Athenians had multiple rhetorical schools which emphasized oratory skills as well as the schools of philosophy.

Xenophon describes the education of the Spartans as such: “There can be no doubt then, that all this education was planned by him to make the boys more resourceful in getting supplies, and better fighting men.” This militaristic style of education differed greatly from the Athenians, which was also described in Aristotle’s Politics: “The citizen should be molded to suit the form of government under which he lives… the character of democracy creates a certain type of citizen.”

Ancient Spartans developed a highly militaristic society to maintain control over a large enslaved population, rigorously training boys from a young age through the harsh agoge system to become disciplined warriors.

Ancient Spartans developed a highly militaristic society to maintain control over a large enslaved population, rigorously training boys from a young age through the harsh agoge system to become disciplined warriors.

Thus, the democratic system of Athens, which encouraged political participation, emphasized skills like rhetoric for students who were meant to participate in the assemblies. The idea that a common ethnicity was derived from education, as Salem suggests, doesn’t account for the many documented differences in the educational systems of Athens and Sparta.

Furthermore, in Menexenus, Socrates mentions the Greek expeditions to Cyprus and Egypt, places where Greek colonies were established. Although the Greek world touched three continents in total, and the Greeks lived among many diverse peoples, the Greeks did not cease to be Greek based on geographic or linguistic differences.

For example, the Greeks of the Ptolemaic dynasty maintained their Hellenism despite being a minority ruling class in Egypt. “Soldiers should record their names, their origin (πατρίς), the units they belong to and the income (ἐπιφοραί) that they receive. Citizens (of the Greek cities of Egypt) should record their fathers, their demes, and, if they are enrolled in the army, their units and source of income. Others should record their [fathers], their πατρίς and the γένος to which they belong.”

The Greeks of Egypt remained connected to their Hellenic ancestry throughout their presence in Egypt. The “πατρίς and… γένος” are translated to fatherland and race, meaning that the Greeks who ventured out of the Greek homeland remained Greek through their ancestry and ethnicity, rather than their language and culture. This historical development mirrors the definition reported by Herodotus, which explicitly mentions a shared blood or ancestry.

Demetra Kasimis, author of The Perpetual Immigrant and the Limits of Athenian Democracy, notes throughout her book how resident aliens were not granted the same political privileges as those who were Greek by blood. “Athens disqualified persons from acquiring citizen status, generation after generation, on the basis of blood, not place of birth.” Kasimis points out how the legal and political rights of foreigners were multigenerational; there was no concept of assimilation or birthright citizenship for non-Greeks or non-Athenians.

The Athenians invented democracy in the 5th century BCE, creating a revolutionary system where free male citizens could vote directly on laws and policies in public assemblies.

The Athenians invented democracy in the 5th century BCE, creating a revolutionary system where free male citizens could vote directly on laws and policies in public assemblies.

Thus, if you were not Athenian, there was no possibility of citizenship being transferred to you at any point in the future. Kasimis further explains that the resident alien was afforded some basic political and economic rights, but their status in the polis was permanently inferior to the citizen. “The blood-based distinction the polis used to distinguish citizen from metic insinuates that an unbridgeable, constitutive gap separates these two relatively free and approximate figures.”

Although the metic – or resident alien – may have been a Greek speaker, worshiped the city’s gods, or observed the Athenian culture to some degree, the Athenians put up permanent barriers to those who did not share a common ancestry or blood with the citizens. In this way, the metic does not meet the definition reported by Herodotus, and the metic was therefore permanently relegated to a class below that of the Athenian citizen due to their ancestry.

Let us also acknowledge that modern scholars agree that legal requirements for citizenship were based on ethnicity; Athens was a very exclusionary society in that sense. Although many non-Athenians lived in Athens, citizenship would never be granted to them or their children. Simply put, to be Athenian meant being born of Athenians. “To be born Athenian: this requirement is the only condition that defines the citizen of Athens. There is no route to becoming Athenian other than being Athenian already.”

Ancient Greeks determined citizenship primarily by birth, granting it to free-born males with parents who were also citizens.

Ancient Greeks determined citizenship primarily by birth, granting it to free-born males with parents who were also citizens.

Since the scholarly consensus supports the idea of blood or ancestry based citizenship as a historical fact, the transition between legal status and political self-identity should be evident. Of course, Athens may be blessed with prolific records and historical data, but that doesn’t discount the fact that the ancestry based citizenship was not isolated to Athens.

Loreaux also states: “Undoubtedly, this version… is one variant of a definition that was shared by much of ancient Greece.” The whole Greek world had some form of ethnic or ancestral based citizenship laws, whether implicit or explicit, and the ancient Greeks were very thorough with their social stratification, which they grounded in ethnicity as well as language, religion, and culture.

Therefore, the ancient Greeks thought of themselves as a distinct group; separated from foreigners through ethnicity, language, culture, and religion. The self-identity of the ancient Greeks was something implicitly understood in the writings of the historians, philosophers, and lawgivers.

The manifestation of their self-identity emerged throughout society, and the collective understanding of the Greek identity produced profound results. Not only were these differences recorded and analyzed in philosophical dialogues, but political decisions were made on the basis of this shared understanding. Internal politics like the granting of citizenship, as well as the decision to reject the Persian alliance, were both political consequences of a shared, understood, and cohesive identity that encompassed all of the ancient Greek people.

Without this mutually understood identity, history would not reflect such a high degree of overlap between the philosophical thought and political decision-making of the ancient Greeks. These ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious similarities, understood by the Platonic dialogues and contemporary sources, help to illustrate how this shared Greek identity was internalized and codified into politics and philosophy.