Greeks are deeply divided on their government’s stance toward the Russia-Ukraine War. Many political parties in Greece are expressly pro-Russia, such as Ellinikí Lýsi and Νίκη, who have campaigned to rebuild political and economic relations with Russia. Meanwhile, the current ruling party, New Democracy, continues to support Ukraine’s military as part of its center-right platform.

Given this political scenario, the idea of realigning all of Greece towards the Russian sphere seems unlikely. Yet the historical ties between Greece and Russia are undeniable.

To be clear, the purpose of this article is not to take a side in the Russia-Ukraine War or make judgments about the conflict. Rather, it is to shed light on the long-standing connections between the Greek and Russian peoples, which are easily forgotten due to the majority of the Greek Diaspora settling in primarily Anglo countries like America, Canada, and Australia.

The history of Greeks in Russia extends back to the sixth century B.C., during the early periods of Hellenic colonization and expansion. Greek presence in the Black Sea, which borders modern-day Turkey and Russia, produced some of our most famous myths, including the race of Amazonian women and the legend of Medea. These tales were set in Greek-populated regions of the Black Sea, such as modern-day Crimea and the Sea of Azov, which boasted a robust presence in the region through prominent cities and dominance in maritime trade. Historians note that after the Islamic conquest of the Levant, the importance of the region increased due to prosperous trade with Byzantium, even after the Greek kingdoms of the region fell.

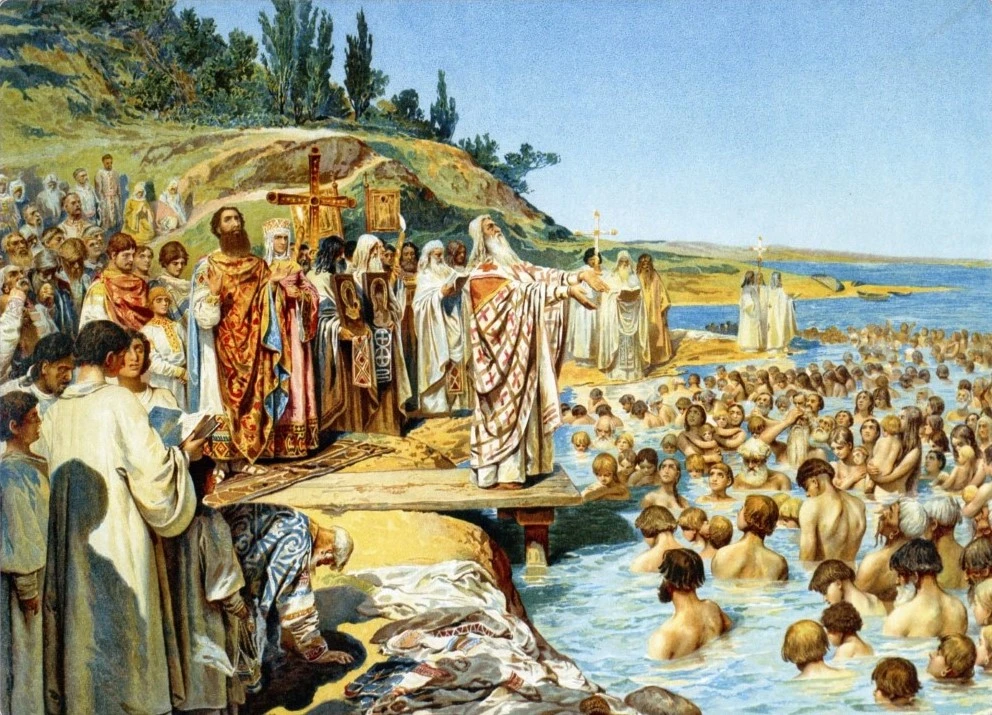

Later, during the medieval era, cultural exchange, religious connections, and military cooperation peaked between Greek and Russian groups. The Baptism of Rus in 988 is considered a pivotal turning point in the Hellenic-Slavic relationship, marking the introduction of Orthodox Christianity to Eastern Slavs after the Greeks successfully converted Prince Vladimir away from paganism.

That same year, The Varangian Guard, an elite unit of faithful bodyguards to the Byzantine Emperor, was established. It consisted of Slavic and Norse Christians who often defended Byzantium from Islamic forces. This period saw trade between the two groups flourish.

Even after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, signaling the end of the Byzantine Empire, connections between Russians and Greeks endured. Amid the spread of Islam, Tsarist Russia became the protector of Christians in the Ottoman Empire, and many Greeks sought refuge within the Russian Empire and found employment in the Russian government as clerics, soldiers, and diplomats. For five centuries, the Russians fought 12 separate wars against the Ottoman Empire, during which many Pontic Greeks collaborated with the Russian Army and welcomed them as liberators from the Turks.

When the Greek War for Independence ignited in 1821, the Russian Empire came to the aid of Greek revolutionaries through military assistance, refugee relief, and diplomatic support. With the formal establishment of modern Greece still two years away, the Battle of Navarino pooled together Greek and Russian ranks to vanquish the Ottomans, which contributed greatly to Greece’s eventual victory. Cooperation persisted between the two groups as Russia continued its dominance in the East and Greek merchants and officials strengthened economic and military ties. This cooperation culminated in the creation of the Greek Volunteer Legion, a force of Evzones led by Christodoulos Hatzipetros, sent to assist the Russian Army in the Crimean War.

However, when Communism emerged in Russia, Judeo-Bolsheviks targeted Greeks because of their devotion to Christianity and nationalistic ideals. The 1937 “Greek Operation” was an organized mass persecution of ancient Pontic Greek communities that had lived undisturbed for thousands of years in Southern Russia and the Caucasus Mountains. Under the direction of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, the Communists killed anywhere between 15,000 to 50,000 Greeks and deported many more to corrective labor camps, or “Gulags,” located in the East.

It must be stressed that this persecution was not necessarily the work of the Russian people themselves, but of their atheist, communist, non-Russian government. Greeks and Russians had lived together in peace and friendship, side by side, for thousands of years, before being upended by the arrival of communists who sought to destroy the ethnic and religious identity of anti-Communist Greeks. As such, it is difficult to consider this to be a Russian-instigated pogrom, but rather a consequence of the same communist ideological forces that persecuted the Russian people and the Orthodox Church at large. Russian national involvement in the ‘Greek Operation’ was not reflective of authentic Russian identity, but the ideological pressures of communism.

Many Hellenes fled the Soviet Union at this time, finding refuge in Greece amongst their countrymen. Simply put, Communism marked a stark turning point in Greek and Russian relations. While Greece has historically been aligned with Russia and the global Orthodox community, the rise of Communism forced Greece to embrace the West and realign its foreign policy to reflect anti-communist ideals.

Despite this, many Greeks remained faithful to the Hellenic-Slavic friendship in subsequent decades, as evidenced by joint cooperation in supporting Serbia during the collapse of Yugoslavia and the preservation of Saint Panteleimon, the Russian monastery located on Mount Athos.

Today, the Russo-Hellenic friendship which has existed for so long is fraying under decades of strain produced by the current geopolitical scenario, and the realignment of Greece towards NATO and America. KTE contends that we Greeks – both Diasporic and native – have much more in common with Russian Orthodox Christians than we have in contrast, thanks to our centuries of allyship. The Greek people should look beyond geopolitics and current political gamesmanship when deciding national consciousness and attitude towards other countries.

As a matter of principle, we believe the relationship between Russians and Greeks is backed by historical precedent. It represents the continuation of a bond that has survived the tests of many centuries and ought to be upheld, regardless of the current zeitgeist or political paradigm.

It is apparent that many people find Greece’s potential geopolitical realignment very controversial. Greece owes much of its present economic performance and political capital to our involvement in NATO and the Western Bloc. However, Greece should not be compelled to choose any side, East or West. We are a unique civilization with a unique history. We should be able to pursue positive political and economic relations with any country, regardless of the wishes of any international entity.